Story by Mary Ann Littell • Portraits by John O'Boyle View the complete magazine | Subscribe to Cancer Connection

When Dave Rodney's B-cell lymphoma didn't respond to standard treatments, it seemed he was out of options. But doctors at Rutgers Cancer Institute and RWJBarnabas Health joined forces to offer the recently approved CAR T-cell therapy, re-engineering the patient's own cells in a laboratory to attack his cancer.

While he relaxed in Jamaica, Dave Rodney (above, left) pondered the future as he realized his blood cells were "half a world away" being re-engineered to fight his cancer.

Turquoise-blue waves lapped the sandy beach at Jamaica’s beautiful Montego Bay, while palm trees rustled in the breezes. A man on horseback rode slowly across the sand. Nudging the horse into the shallow water, he gazed at the horizon. What was he thinking?

“Here I am, riding a horse in Jamaica,” says Dave Rodney. “Half a world away, my blood cells are in California, being re-engineered into cancer-fighting cells that will keep me alive for many years to come. I’m thinking I must be living in the future, or at least on another planet!”

At 62, Rodney enjoys the best that life has to offer: travel, culture, music, fabulous resorts, and great food. He earns a living at it too: he’s a public relations entrepreneur, travel consultant and writer, music producer, and concert promoter. His primary focus is Jamaica and the Caribbean, and he spends a lot of time there.

This world traveler has just completed the journey of his life - his cancer journey.

In August 2017 Rodney was diagnosed with recurrent diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Treated with chemotherapy, he relapsed quickly and didn’t have a good response to his next treatment. His future looked bleak. Patients with this disease can be cured if they are successfully treated with first line chemotherapy. However, patients who relapse and then don’t respond well to further chemotherapy face a poor prognosis, surviving an average of only six months.

While it’s certainly bad luck to have diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Rodney had a bit of good luck too. He was diagnosed at just the right time to benefit from a lifesaving new treatment, CAR T-cell therapy, in which a patient’s own immune cells are re-engineered to treat their disease.

Until this past year, people with resistant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma had very limited treatment options. However, with the FDA approval of CAR T-cell therapy in 2017, patients have a mighty new weapon in the arsenal to fight their disease. Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, in partnership with Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (RWJUH) in New Brunswick, an RWJBarnabas Health facility, is one of only two certified programs in the state to offer CAR T-cell therapy.

See the full video component of Dave's story

View more patient stories at cinj.org/patientstories

Rodney was the first patient to undergo this procedure at RWJUH in November 2018. “Being the first was nerve-wracking,” he admits. “The hospital had never done this before, but I was won over by the compassion, professionalism, and skill of my medical team. And as it turned out, I made the right decision.”

Rodney was born and raised in Jamaica. As a young man he studied in France on scholarship, learning Spanish, French and German. Returning home, he went to work for the Jamaica Tourist Board. “I gave visiting journalists information they needed for their stories, whether the topic was cuisine, dance, culture, reggae, resorts or beaches,” he says. “I was the happiest man in Jamaica, with the coolest job. I had no plans to move anywhere, least of all New Jersey.”

Transitioning into the music business, he hosted such artists as Patti LaBelle and Stevie Wonder on the island and frequently traveled to New York City, a hub for the music industry. As he signed his first reggae artist to a recording contract at Atlantic Records, he found it increasingly difficult to do this work from Jamaica. So in 1990 he relocated first to East Orange, and later to South Orange, New Jersey. He continued to build his business, and in his free time, worked out at the gym and played tennis.

Dave Rodney (above) was the first patient to undergo CAR T-cell therapy at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, in partnership with Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, in November 2018. "Being the first was nerve-wracking," he admits

In August 2017 Rodney began a rigorous workout regimen with a new personal trainer. The next day he felt something strange in his lower abdomen – not pain, just an uncomfortable feeling. He assumed he’d pulled a muscle, but the discomfort persisted. By coincidence he was scheduled to see his physician for a routine visit. His doctor advised him to go to the emergency department at Saint Barnabas Medical Center (SBMC) in Livingston, also an RWJBarnabas Health facility, as a precautionary measure.

David M. Edwards, associate vice president for development at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey talks about how philanthropy can impact cancer care and CAR T-cell therapy is just one example.

While there, Rodney had a full evaluation, including scans that showed an abdominal mass. Admitted to the hospital for additional tests and a lymph node biopsy, he was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. This fast-growing cancer begins in white blood cells called lymphocytes. Despite its aggressiveness, it’s considered potentially curable.

“Being diagnosed with cancer was a shock,” he says. “I’m by nature a calm person, so I took it in stride and planned my next steps.”

Under the care of SBMC oncologist Andrew Brown, MD, Rodney learned that there are many types of lymphoma. Some are aggressive while others advance slowly and don’t even necessarily need treatment, just monitoring. “His was a high-grade lymphoma, so we would try to cure him with chemotherapy,” says Dr. Brown.

Unfortunately, that first round of chemo had little effect on Rodney’s lymphoma. A second round with a different medication also proved unsuccessful. “When there is residual lymphoma left after completing chemotherapy, the prognosis changes from, ‘We really think we’re going to cure you,’ to ‘We’re going to try our best,’” says Brown. “In someone young and healthy like Dave Rodney, the standard of care was stem cell transplant. But now we also have CAR T-cell therapy to consider.”

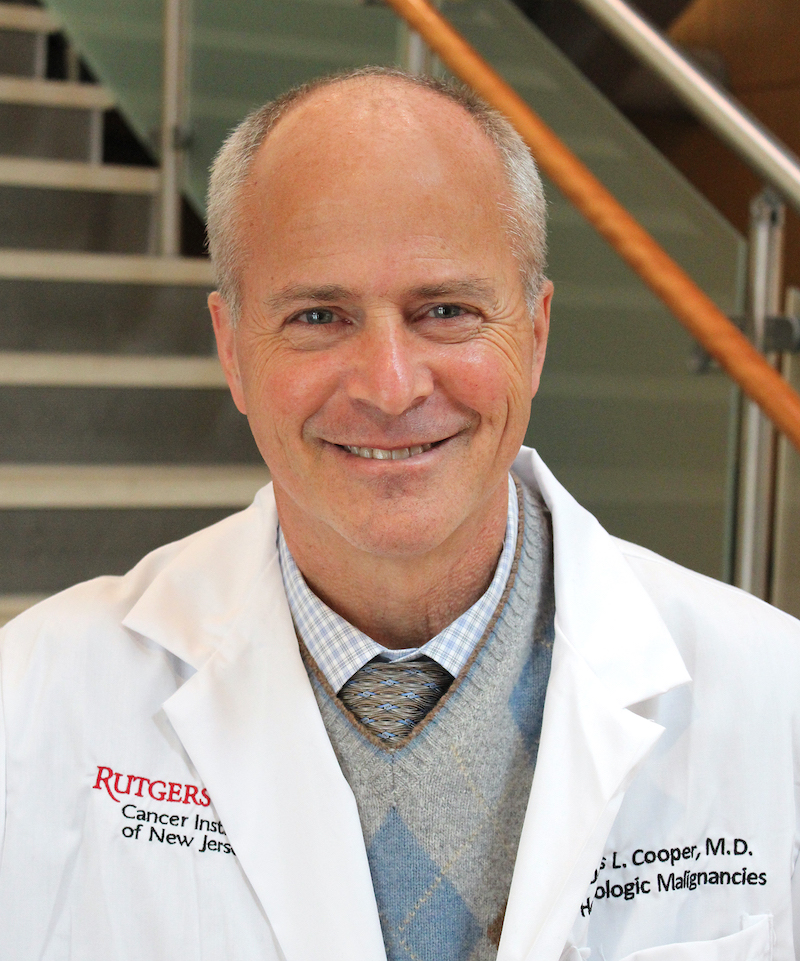

Dennis Cooper, MD, chief of Blood and Marrow Transplantation at Rutgers Cancer Institute

The unique partnership between RWJBarnabas Health and Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey provides cancer patients with the newest, most sophisticated therapies and a seamless transition to the next level of care. Brown referred Rodney to Dennis Cooper, MD, chief of Blood and Marrow Transplantation at Rutgers Cancer Institute. Dr. Cooper’s areas of clinical expertise include multiple myeloma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and he’s known for his innovative work in stem cell transplant.

Rodney met with Cooper in March 2018. “We talked about stem cell transplant and Dr. Cooper also told me about CAR T,” says Rodney. “It was so new they hadn’t started doing it there at that time. I was fascinated and took out my phone to do a brief interview with him. I was afraid I’d forget what I’d heard.”

Further review of Rodney’s case indicated that CAR T-cell therapy offered the best chance for a cure. “Patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who do not achieve a complete remission with further chemotherapy generally have a poor outcome with stem cell transplant,” explains Cooper. “Therefore, we offered him CAR T-cell therapy. This treatment was approved for patients with chemotherapy-resistant disease. Approximately 70 percent of these patients will respond to CAR T-cells and some 40 percent may be cured.

“We thought Mr. Rodney would be an excellent first patient,” says Cooper, who is also a professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. “He’s fit and in good health. He’s also very articulate, able to describe his symptoms and interact with the staff. With a positive outlook, he welcomed the opportunity to participate in a new medical frontier.”

On his next visit Rodney discussed the procedure’s pros and cons with Cooper and nurse clinician Jacqueline Manago, BSN, RN, BMTCN. “They were very honest and open,” he says. “Yes, I’d be the first. But on the plus side, the staff was well prepared. Many eyes and ears would be watching me to make sure everything went well. What they said made perfect sense, so I was sold.”

Patients having CAR T-cell therapy first undergo a procedure called leukapheresis, in which their lymphocytes are collected in a process similar to dialysis. The cells are then sent to a laboratory in California to be re-engineered so that they are programmed to attack a target on the lymphoma cells but not on normal cells. This process takes about three weeks.

"It’s impossible to describe the high level of care I had. You’d have to experience it for yourself: the professionalism, expertise, warmth and caring. These are the best people on the planet!”

Just before patients receive the genetically altered CAR T-cells, they are given a relatively mild pre-treatment chemotherapy to clear their blood of lymphocytes that could compete with the CAR T- cells. After that, the re-engineered cells are infused back into the body to do their work.

Between the time that he had his cells collected and the beginning of the mild chemotherapy, Rodney went on a trip to Jamaica for a concert promotion. “I danced on the beach and zipped around the island, thinking about my cells zipping to California,” he says.

Returning home, he underwent the mild pre-treatment chemotherapy with Brown at SBMC and was then admitted to RWJUH for his infusion in November. “It was very simple, like a quick transfusion,” he says. He remained in the hospital for two weeks (the national average for this procedure), battling common side effects that included short-term memory loss and high fevers, which resolved quickly.

Before he was discharged, Rodney threw a tropical-themed party for the hospital staff, bringing in a Jamaican chef to cater a delicious lunch of jerk chicken, rice and peas, and other island delights. “I wanted to thank them for all they did,” says Rodney. “It’s impossible to describe the high level of care I had. You’d have to experience it for yourself: the professionalism, expertise, warmth and caring. These are the best people on the planet!”

While it is too early to know Rodney’s prognosis, his medical team is encouraged by how good he feels and his quick return to normal activity. “CAR T-cells remain in the body attacking malignant cells long after the infusion is given,” explains Cooper. “That’s why these cells are sometimes called a ‘living drug.’ We know patients’ PET scans may continue to improve over the first year, too. In patients who achieve a remission scan at one year after treatment, very few appear to relapse.”

When Rodney’s friends and colleagues learn what he’s been through, they’re amazed that he hasn’t missed a beat. “Work was a huge part of my therapy,” he says. “It kept me going through a difficult time. And now I’m back to being my usual busy self, working, traveling, and enjoying life.”

An Emerging Immunotherapy

An Emerging Immunotherapy

CAR T-cell therapy is a type of immunotherapy known as “adoptive cell transfer” treatment, in which specialized white blood cells (T-cells) whose job it is to attack foreign items in the body, are taken from the body, re-engineered in the laboratory, then reinfused into the body to attack the cancer. At Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, clinical trials examining adoptive cell transfer therapies are being explored. One such trial is evaluating the safety and effectiveness of T-cells grown from a patient’s tumor (then placed back in the body) in the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck that has returned or spread to other parts of the body.

“By reprogramming these cells and placing them back into the patient, we are enhancing the patient’s ability to fight the cancer using the body’s own natural defenses,” says the trial’s lead investigator Malini Patel, MD, hematologist/oncologist at Rutgers Cancer Institute and assistant professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.